How Wolves Changed Yellowstone’s Rivers: Understanding Trophic Cascades

Stop!

Seriously — hit pause for a moment. Have you ever looked at something in nature and thought, “Yeah, okay, that seems pretty simple…” only to find out it’s actually part of a huge, hidden chain reaction?

That’s the kind of thing that we’re going to talk about today. Nature is full of secret connections, and once you’re able to spot them, the bigger picture becomes way more interesting.

One of the most fascinating examples of a small change making a big difference happened in Yellowstone National Park. Wolves were removed from the park without fully understanding how that single action would completely change the forests, meadows, and even the rivers.

This story will show you just how powerful and interconnected nature truly is. Come with me to explore this lesson in ecology, balance, and the surprising ways that life on Earth fits together.

A Park Without Wolves

For thousands of years, wolves thrived in Yellowstone. They hunted elk, which kept herds on the move, and played a major, unnoticed role in the park’s ecosystem.

However, in the early 1900s, people began to fear wolves. Wolves were viewed as dangerous predators. Hunters and government programs were implemented to remove wolves from the park entirely.

By 1926, there were no wolves left in the park.1 What could possibly go wrong when a top predator disappears?

As it turns out, a lot can go wrong.

It would take years before Yellowstone truly learned of the damage that removing them had caused. Without wolves roaming the park, elk populations grew drastically.2 Elk ate plants like grasses, shrubs, and even young trees.

With no predators to keep elk populations in check, they began to overgraze the land.2 Small and young plants struggled to grow, putting strain on the ability of forests to recover from grazing.

Over time, the consequences of removing wolves became undeniable.

Willow and aspen trees stopped growing tall, as elk frequently ate them before they could mature into full trees. With willow trees declining steadily, beavers were unable to rely on them for food or for building dams.

Fewer trees also meant fewer nesting areas for birds. Additionally, shrubs produced berries that many animals relied on for food, but elk ate them. This left many different species with dwindling reliable food sources.

The entire Yellowstone ecosystem began to weaken. Nature was out of balance.

Return of the Wolves

In 1995, scientists and wildlife experts finally intervened. Wolves were brought back to Yellowstone. Fourteen wolves were released into the park from Canada. The next year, they released another 17 wolves.1

These wolves began to form packs, raise pups, and hunt elk – the major source of the damage that had occurred.

What happened next can only be described as a huge sigh of relief.

The wolves reduced elk populations and forced them to change their behavior. They became more cautious, spending less time in open valleys and near riverbanks, where they could be easily hunted.2

This shift in behavior finally allowed plants to recover in places where they hadn’t grown tall in decades.

Plants Make a Comeback

After elk stopped heavily grazing riverbanks and meadows, balance began to return to the forests.

Young aspen and willow trees shot upward, growing several feet within a few years.3 Forests recovered their greenery and invited much-welcomed guests.

Nesting sites flourished; songbirds returned, and woodpeckers feasted on pests.

Shrubs grew back their barren branches, returning taller and thicker with an abundant supply of berries. Food was no longer scarce for animals of all sizes. It was plentiful enough for the entire ecosystem to begin returning to normal.

Beavers: The Ecosystem Engineers

Not only did plants begin to flourish, but the most impressive recovery of all involved Yellowstone’s beavers.

Before wolves had returned to Yellowstone, beaver colonies were scarce. It didn’t have enough willow trees to build dams or lodges and was on the verge of losing its last remaining members.

But as willow saplings grew into mature trees, beaver populations started to make a comeback. Now, Yellowstone has many beaver colonies that have transformed the landscape.

The beavers built more dams that slowed the water, creating ponds and wetlands. This provided homes for fish, frogs, and insects. These watering holes created a haven for migrating birds to return to.

How Wolves Changed Rivers

So, how exactly did wolves change the rivers? Can one animal really reshape an entire landscape?

Yes. It can.

Though the effect was indirect, wolves changed the rivers by forcing elk to migrate more often, allowing plants to grow back along the riverbanks. Their roots helped keep the soil in place and reduce erosion.

Rivers became narrower and deeper while water flowed more smoothly. The landscape stabilized and diversified, with plenty of animals returning to a once-barren land.

Furthermore, with an abundance of trees encouraging beavers’ return, the dams they built reshaped the waterways.

All of these changes were only possible because wolves changed where elk grazed.

This chain reaction is called a trophic cascade.

What Is a Trophic Cascade?

You might be wondering, what is a trophic cascade? Why is this so important to the ecosystem?

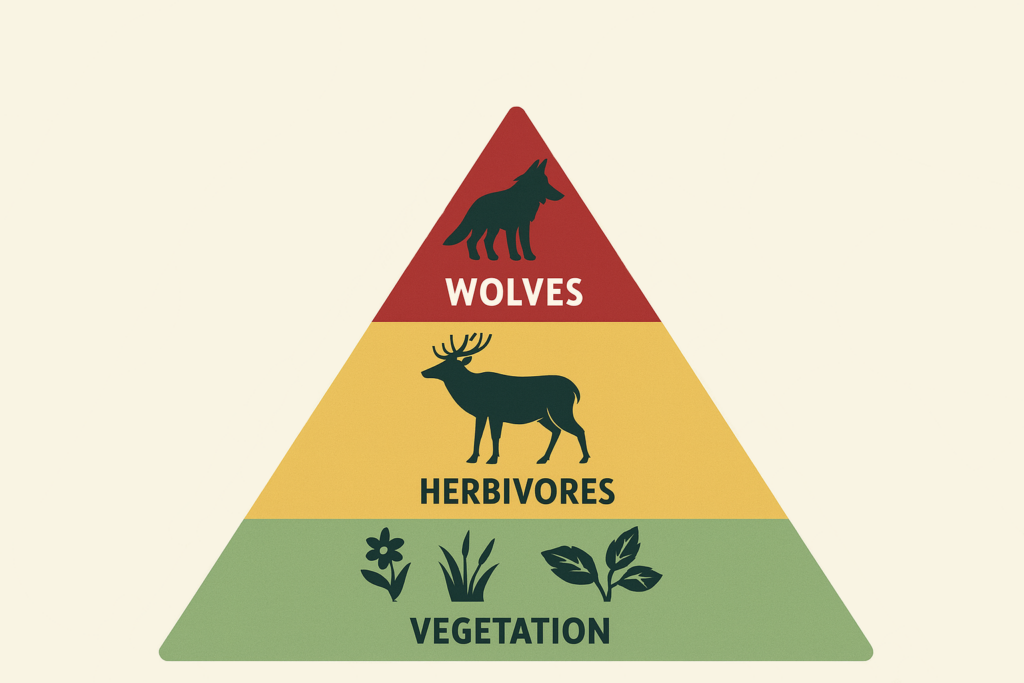

Well, a trophic cascade is an ecological process that starts at the top of the food chain and trickles down, affecting many other species.4

Let’s take a look at how this applies to Yellowstone.

You can break it down piece by piece like this:

- Wolves affected…

- Elk! Which affected…

- Plants, which affected…

- Beavers, which affected…

- Rivers, wetlands, birds, fish, insects, and more!

The effects from one animal cascade down to other organisms, like water trickling down a stream.

You can also think of it like dominoes. When one domino is knocked over, the rest begin to topple. One change leads to another, which in turn leads to an unforeseen number of changes.

Why This Story Matters

Why does this story about Yellowstone, a place you may have never visited, even matter?

It’s important because it teaches us a lesson about the interconnectedness of nature.

Even though predators may seem scary, they help keep ecosystems stable and healthy. Furthermore, Yellowstone’s recovery showed that nature can be resilient when given the opportunity. Decades of damage can be recovered in as little as a few years if change is encouraged.

Yellowstone faced a hardship spurred by fear, but today it is one of the most studied ecosystems in the world. Scientists continue to use Yellowstone National Park as an example to understand how ecosystems work.

Final Thoughts

One thing about this story is clear: the return of wolves transformed Yellowstone in unexpected ways, quite literally moving rivers.

This story wasn’t just about cool science facts, but a simple reminder that nature is full of hidden connections. When we protect wildlife and ecosystems, we’re protecting the balance that keeps Earth healthy.

When wolves were reintroduced into Yellowstone, nobody told them to “fix” the damaged ecosystem. Nature figured that out on its own. Their presence reshaped forests, invited animals to call Yellowstone home, and even altered the flow of rivers.

It’s an astonishing example of how a single species can influence an entire world.

If you ever visit Yellowstone, listen closely. You might hear a distant howl echoing through valleys – a reminder of the very thing that healed the park you’re standing in.

Hands-on Activity, Definition Sheet, and Printable Article

Trophic Cascade Activity

Definition Sheet

Printable Article

Sources:

1. National Park Service. (n.d.). Wolf restoration in Yellowstone National Park. U.S. Department of the Interior.

2. Middleton, A. D. (2014). Elk ecology and wolf predation in Yellowstone National Park. University of Wyoming.

3. Ripple, W. J., & Beschta, R. L. (2012). Trophic cascades in Yellowstone: The first 15 years after wolf reintroduction. Biological Conservation, 145(1), 205–213.

4. Yong, E. (2014). The trophic cascade myth. Smithsonian Magazine.